The popularity of a once-obscure senator from Vermont is the product of years of organizing and agitation by social movements.

Back in the days when New York’s Zuccotti Park pulsated with the chants and drumming of the Occupy Wall Street encampment, it was hard to complete too many conversations without encountering the anarchist catchphrase “diversity of tactics,” used to indicate an understanding of property destruction as a legitimate political act.

Rare, though, was the occupier who was prepared to include voting, campaigning, and running for office as tactics in that diversity. This was perhaps understandable: in the wake of the Tea Party insurgency, it rightly seemed to many that the political moment was prohibitive of the sort of candidacies that might be said to embody the Occupy credo, “Another world is possible.” Electoral work in the political context of 2011 seemed a futility at best — or, more perilously, a sinkhole for time and energy that could be spent on more vital political activities.

Through the deployment of diverse tactics, social movements have, in the intervening years, performed some of those vital activities. The result is a marked shift in the political terrain. Occupy’s marches and assemblies shook the neoliberal consensus around finance. Low-wage workers’ strikes and pickets reinvigorated the fights for workers’ rights and against poverty. The Movement for Black Lives’ uprisings rattled the hegemony of “tough on crime” politics. The Climate Justice movement’s divestment campaigns and physical infrastructure blockages threatened the reputation and profitability of the fossil fuels sector. The sit-ins of the “No Papers, No Fear” undocumented youth movement forced consequential executive action.

In the last five years, movements have taken dynamite to the borders of political consideration, blasting open significant space on the left.

Improbably, the foremost entrant into that space in the current election cycle is a slightly disheveled senator from a tiny, rural, white New England state, his age a better fit for a retiree than an upstart. Bernie Sanders isn’t the first guy you would have picked as the beneficiary of the last five years of agitation. Yet, everywhere he goes, throngs wait for hours to cheer and chant and shout “Yuuuge” at the candidate, whose small-dollar donation effort has set new fundraising records. Though he is not the leader social movements might have imagined would occupy the space created by their diverse tactics, his popularity is a testament to their efficacy.

He won’t be the last. Not only will the political terrain created by social movements accommodate further political advances, the movements aren’t even done creating it. Organizations growing out of these social movements continue to organize chapters, build bases, perform political education, enact dramatic direct actions, and release policy programs. Perhaps there will be a wave of “Sanders Democrats” threatening the dominance of capitalist interests in that party. Perhaps a new party, or a new non-party-based political identity, will emerge. Perhaps formal socialist parties will acquire seats in various political bodies. Probably, all three will happen, and more that can’t be foresees: there is no reason to suppose electoral tactics should or will be less diverse than those available to street protesters.

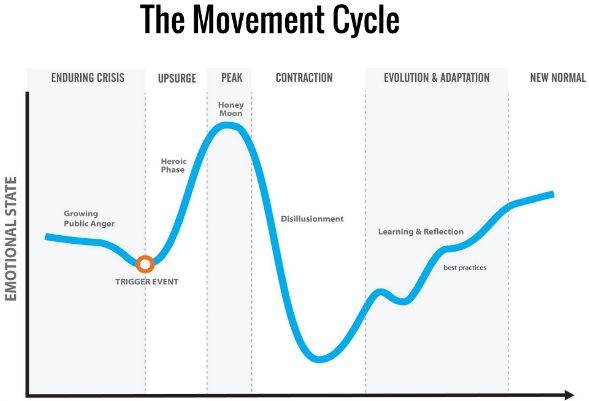

The purpose is to continue on to a “new normal,” the final stage in the “Movement Cycle” articulated by Movement Net Labs (MNL), a think tank focusing on the nature and structure of decentralized movements that grew out of Occupy.

Everyone is by now familiar with the exuberance of the heroic phase and honeymoon, but where most commentators have conceived of the contraction as a sign of failure, the MNL model conceives of it as an inevitable, if painful, phase in a success. The denouement lands on higher ground than the expansion departed from. That differential appears as “movement infrastructure”: organizations, networks, technological tools, and associations forged in the crucible of the movement moment — like MNL.

The Bernie Sanders campaign, powered so heavily by the decentralized contributions of organizations and networks — prominently, People for Bernie, an Occupy outgrowth — exhibits all the signs of a movement moment. The comedown may be harsh, but it will have landed us at a new normal. The higher we climb, the easier it will be to envision the other world Occupy insisted was possible.

This content was originally published by teleSUR here.